Evaluating NFL Draft Picks

Premium Positions, Big Boards, & Approximate Value

A year ago, both the Carolina Panthers and Houston Texans had eerily similar draft strategies: each team drafted a quarterback, traded up for an edge rusher, and selected a wide receiver within the first three rounds. Despite these parallel approaches, their outcomes diverged dramatically over the subsequent NFL season.

The Panthers stumbled to a league-worst 2-15 record, leading to the dismissal of general manager Scott Fitterer. Meanwhile, under Nick Caserio’s team building approach the Texans went 10-7 and won a playoff game, earning Caserio widespread acclaim for his draft evaluations. This article explores the intricacies of different draft processes and examines their outcomes.

The Fitzgerald-Spielberger Trade Value Chart builds off on the work of Cade Massey and Richard Thaler’s in The Loser’s Curse. Their chart represents the value of each pick based on second contracts. However, teams predominantly still use the Jimmy Johnson chart when trading draft picks, creating a market inefficiency.

Chase Stuart also developed a trade chart using Approximate Value (AV). Instead of focusing on second contracts, Stuart appraised the value of each draft pick based on player performance. Both Fitzgerald-Spielberger’s and Stuart’s charts appropriately value mid-round draft picks.

In this analysis, the values from the Fitzgerald-Spielberger trade chart are converted into a blind surplus. This blind surplus represents the average post-rookie contract value for a few picks before and after each draft pick. Approximate Value (AV) is also transformed into an annual dollar amount. This will be referred to as the Surplus Value Gained (SVG). Both of these values are deducted by the player’s contract value over the course of their first four years in the NFL. These two metrics are then used to evaluate how effective general managers are at adding talent through the draft.

Positional Value & Consensus Big Boards

Last year, Ben Baldwin developed a Draft Value Curve that excluded quarterbacks. His approach was similar to Fitzgerald-Spielberger with a focus on second contracts. He identified that certain positions, known as premium positions, provide more value earlier in the draft. These premium positions typically include QB, OT, WR, IDL, and ED.

Teams on average prioritize premium positions at a higher rate in the first 100 picks of the draft. Should premium positions be taken more frequently in the first few rounds? If so, how many prospects that play a premium position are worth a top 100 selection each year?

The scarcity component means general managers should in theory attempt to trade back if premium positions on their board aren’t available in order to recoup value.

Yearly positional weights are generated based on the top 5 players in Annual Average Value by position. The Annual Average Value is converted to a percentage of that year's salary cap to account for inflation. These cap percentages are then multiplied by a factor of 10. This weight can be applied to blind surplus to account for discrepancies across positions.

Another factor to consider is the Consensus Big Boards, which are fairly accurate at predicting when prospects will be drafted. However, there are several cases where players unexpectedly fall or rise on draft night.

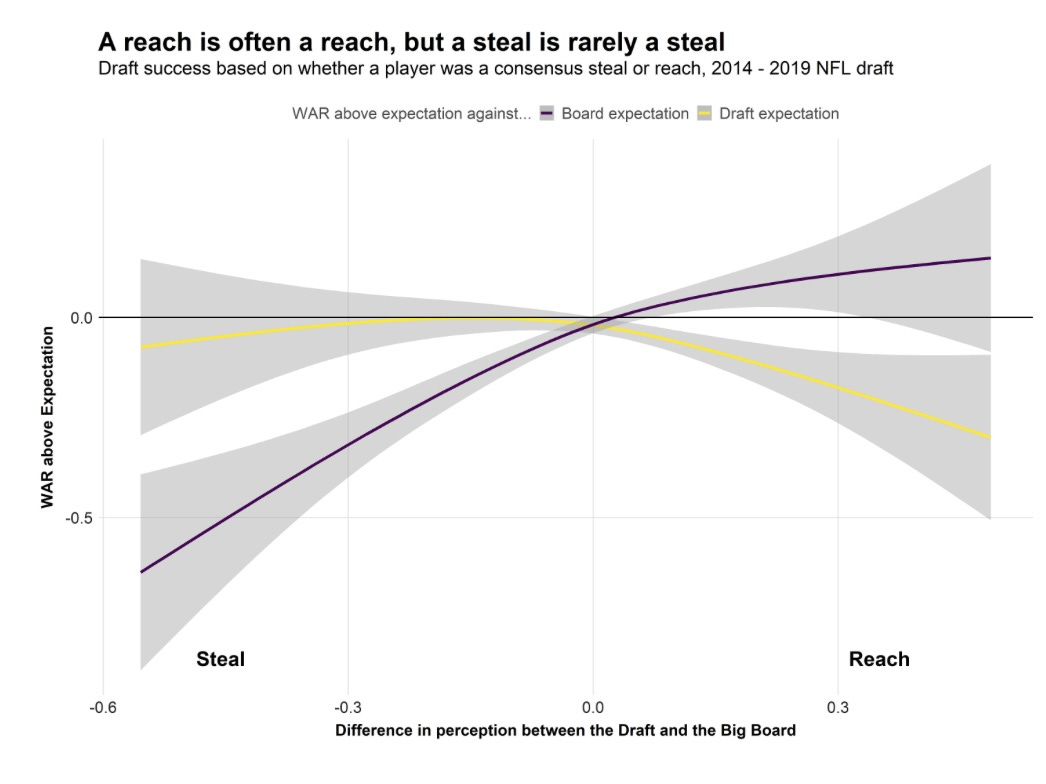

Timo Riske with PFF analyzed reaches and steals back in 2021. When a team reaches for a player, they typically underperform. However, this isn't always the case, as there are plenty of instances where players who were considered reaches overperform relative to their draft status.

Prospects that fall aren't necessarily steals either; they fall for reasons such as medical concerns, character issues, or other factors that may not be apparent during the draft process. Typically, their production aligns with where they are ultimately drafted.

Jason Fitzgerald also analyzed reaches and steals based on consensus big boards. Players who jumped over 100 spots typically secured a second contract worth around $4M, whereas those who fell over 100 spots generally received a contract close to the league minimum. This aligns with Timo Riske's findings. Although reaches do not have the best hit rates, they are not as catastrophic as the media might suggest. Similarly, steals do not always significantly outperform their draft status at the next level.

These previous studies by Timo Riske and Jason Fitzgerald used Arif Haasan’s Consensus Big Board. For this study, Jack Lichtenstein’s Consensus Big Board from 2016 to 2023 is utilized. If a prospect is reached for, the blind surplus of the pick is based on the big board ranking to penalize the front office for selecting the player too early. If a prospect falls, the blind surplus reflects their actual draft status rather than the big board ranking.

The blind surplus, after being weighted for the Consensus Big Board, is factored by the positional value discussed earlier to create Weighted Position Surplus (WPS). The year-to-year stability of this metric has a Pearson's R of 0.17, indicating a weak correlation that is identical to that of Blind Surplus; the expected value of the pick based on second contracts.

This approach identifies how general managers allocate their team's draft capital and rewards them for selecting premium positions without reaching for prospects. In theory, this sounds like a good starting point, but how does it translate to actual performance? Is it predictive of how certain draft classes will perform in the future?

Approximate Value to Annual Average Value

The expected value for draft selections is captured in dollars through Weighted Position Surplus (WPS). Pro Football Reference's Approximate Value (AV) is the performance metric used to help identify the Surplus Value Gained (SVG).

The rolling average of the top 5 AV scores by position from Pro Football Reference since 2011 for players in the first 4 years of their NFL careers is calculated. This proxy is used to divide a player’s AV score, which captures the percentage of production relative to the position played.

This AV percentage is then multiplied by the going market rate. The market rate is defined as the top 5 Annual Average Value (AAV) for each position. This calculation for Surplus Value Gained transforms player performance into dollars to easily compare with Weighted Position Surplus.

Surplus Value Gained

Quarterbacks offer the most surplus value in the first round by a wide margin. However, in the later rounds of the draft, their average surplus value drops dramatically despite the value of the position. In the first round, premium positions offer a little over $6M in surplus value over the course of their rookie contract compared to non-premium positions. In later rounds, that difference in surplus between premium and non-premium decreases to around $3M.

These findings are in line with Ben Baldwin’s research discussed previously. Positional value appears to converge around the end of Day 2 and the start of Day 3. The position a team selects seems to matter more in the first few rounds of the draft compared to the later rounds.

In essence, premium positions should be the focus with premium draft capital. What does the distribution of Surplus Value Gained (SVG) look for different positions within the first 100 selections?

The above graphic can be a bit deceiving because it doesn’t tell us how many players were taken at a particular position, the average draft allocation allotted, or the hit rate.

A player is considered a hit if their Surplus Value Gained is greater than or equal to their Blind Surplus. This proxy identifies if the player outperformed their draft status based on the Fitzgerald-Spielberger chart. The 95th percentile outcome for SVG highlights right tail outcomes for each position group.

Interior defensive linemen (IDL) and edge rushers (ED) are taken at a significantly higher rate with a lower amount of hits than offensive linemen. Are front offices aware that defensive linemen are harder to project to the next level and take more swings at that position because of it? Does that in turn increase the market value for defensive linemen that do hit?

On another note, it doesn’t seem smart to invest premium draft capital into positions such as safety, running back, and cornerback that offer limited surplus value and have lower hit rates. That production could more than likely be replaced in later rounds or free agency.

Evaluating General Managers

Weighted Position Surplus identifies how a general manager utilized their resources and provides a reasonable expectation for their draft selections. Whether they reached for certain prospects or spent draft capital on premium positions.

Surplus Value Gained informs us how well a player performed on their rookie contract. Weighted Position Surplus has a positive correlation with Surplus Value Gained with a Pearson’s R of 0.35.

Ozzie Newsome is one of the greatest general managers in NFL history, and he hit on one of his best draft classes in his final year, 2018. It’s unfortunate that general managers with good processes and draft capital, such as Joe Douglas and Scott Fitterer, have simply made poor evaluations of the players they've selected.

Surplus Over Expected is derived by subtracting Weighted Position Surplus from Surplus Value Gained. The annual values in 2023 dollars for all three metrics are highlighted in the table below. General managers with a Surplus Over Expected of $8M or greater all made the postseason this past season.

Notable general managers such as Howie Roseman and Eric DeCosta generate surplus in other ways—through trades, contract structuring, and other methods not covered in this analysis. The table above depicts Tom Telesco’s tenure with the Chargers. He is currently the general manager for the Raiders.

Pitfalls and Takeaways

One of the pitfalls of using Approximate Value is that it disproportionately favors offensive positions. Evaluations of the offensive line are based more on offensive production than on individual merit. While some drawbacks of Approximate Value are mitigated by considering a player’s first four years in the NFL, this is not the case for draft classes since 2021, who have not yet completed their rookie contracts.

If a general manager cannot confidently select a premium position in the first round, they should consider trading back to a point where selecting a non-premium position would be less detrimental. Alternatively, trading up for a premium position might be advisable if the price is right. Additionally, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that selecting a non-premium position after the first round is not as harmful.

Wrap Up

Second contracts and Approximate Value offer insights into what we can expect from draft classes and their subsequent outcomes. The aim of this analysis was to convert these varied metrics into a uniform unit. By expressing everything in dollars, it becomes easier to identify which general managers are generating the most surplus.

With metrics such as Blind Surplus, Weighted Position Surplus, and Surplus Value Gained, trades involving picks and players can be assessed through a similar lens. This approach paves the way for future endeavors that will provide additional avenues to evaluate how effectively general managers generate surplus.